December 20, 2025

Canada’s first population decline is being blamed on temporary residents leaving, but that overlooks a deeper structural issue: a record outflow of citizens too. Statistics Canada (StatCan) data shows emigration, the act of citizens or permanent residents relocating abroad, surged in Q3 2025. The unusual record outflow over the past year has only seen anything like this twice in history. All three of these periods reveal the same issue—the misallocated capital that occurs during a real estate bubble.

Canadian Emigration: Why Outflows of Locals Is Really Bad News

Canadian emigration is when citizens or permanent residents leave for another country. People come and go—it happens. It turns into a problem if these outflows are elevated and persistent. Policymakers tend to shrug it off by focusing on net flows: losing one Canadian isn’t a problem if we can manufacture two new ones. However, this is a huge mistake.

Persistent emigration isn’t distributed randomly—it’s a sign a country is losing its edge. The people leaving tend to be prime-aged workers in highly coveted fields, the group Canada can least afford to lose. On paper, immigration may seem like a fix. In reality, the same conditions pushing talent out will eventually push those immigrants out as well.

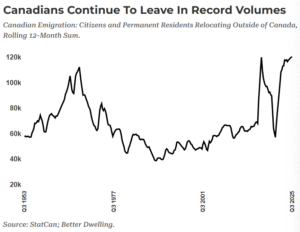

Canada’s unusual emigration surge continued into the latest population estimates. The country recorded 41,203 emigrants in Q3 2025, up 0.9% from last year. Growth is stable, but stable at an elevated level that’s roughly 30% above pre-pandemic norms. Canada has only seen Q3 higher once, in 2017. Put a pin in that, we’ll circle back after annual data.

Canadians fleeing for greener pastures have climbed sharply in recent years. There have been 120,401 emigrants over the 12 months ending in Q3 2025, up 2.3% from last year. It’s now at the largest outflow on record, and not just for Q3, but for any 12 month period in Canadian history.

Emigration Has Only Been Close To This Level Twice Before

Canada rarely sees large outflows, as it’s better known for attracting immigrants, not losing citizens. Today’s surge only has two comparable periods on record: peaks in 1968 and 2017. Dig into newspaper archives from those years and the similarities to today are striking.

The 1968 peak is attributed to professionals fleeing to the US. That was the year that Canadians lost priority access to US jobs, as new immigration rules kicked in. It’s a period of “brain drain,” but the framing tends to present it as an issue of greed, with our talent looking for money. It was more about our greed, and the misallocation of resources that resulted from—drumroll—a real estate bubble.

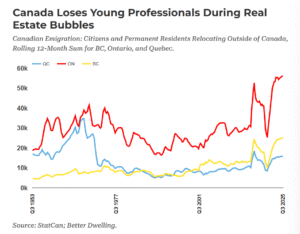

In the 1960s, young professionals faced a clear choice: move to the US and join a technology and engineering boom or stay behind and stick it out with a housing bubble. We’ve previously highlighted that newspaper archives show a speculative land bubble in the 1960s. In fact, by 1967 there were calls for a vacant land tax to help curb the urban land hoarding. It’s not a coincidence that Ontario and Quebec accounted for most of that emigration.

The 2017 surge follows a similar path, coinciding with a regional real estate bubble. Roughly 80% of emigration at the Q2 2017 peak were from just three provinces—BC, Ontario, and Quebec. All three had just seen a sharp collapse in affordability, and this is right around when two of those provinces implemented non-resident speculation taxes to cool the speculative mindset. We call the outcome “brain drain,” but it wasn’t competition that pushed talent out—it was a housing bubble and the massive misallocation that follows.

The pattern is repeating today. Brain drain makes it sound like we’re losing a race, but Canada isn’t. It’s choosing to funnel resources to support short-term speculative values, and then asking professionals to accept falling a decade or two behind their global peers. These professionals aren’t fleeing, but choosing not to be exploited.

-Stephen Punwasi

Co-Founder and chief data nerd at Better Dwelling. Named a top influencer in finance and risk by Thomson-Reuters.